Lichen: Some love for the small things

August 2, 2020 | Samantha Pedersen

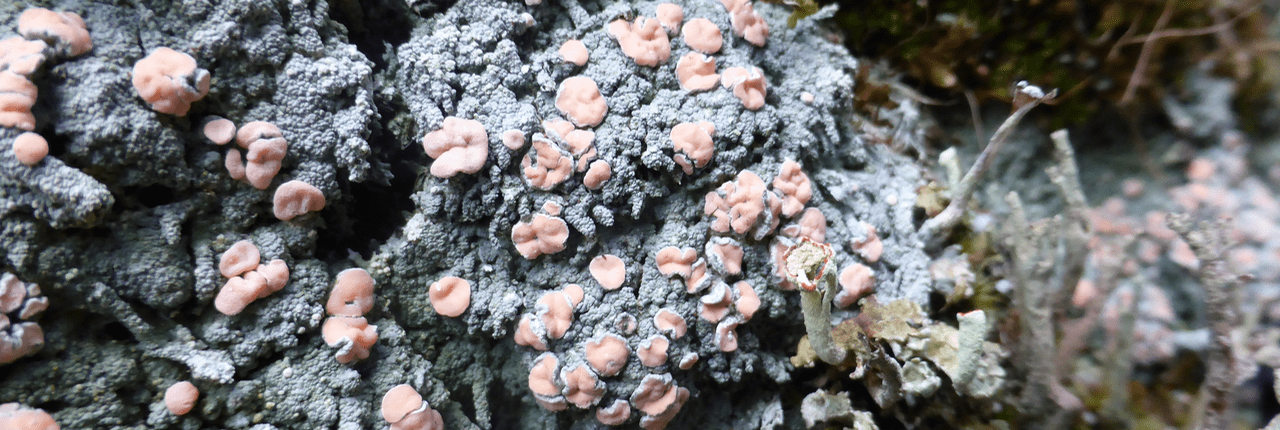

Fairy Barf Lichen (Icmadophila ericetorum), Photo by Samantha Pedersen

From whales and their astonishing size, bald eagles and their majesty, to otters and their loveable, cuddly faces, why do we – naturalists and the general public alike – have such a collective focus on the cute and charismatic? Perhaps it’s because in many cases, both the exciting facts and the ecological qualms of showy creatures have mass appeal that draws more people to their issues. The triumphs and the tragedies of these showy species captivate and move audiences in a way that little things – more inconspicuous things – often do not. Why is this? To me, the inconspicuous are no less beautiful and are certainly no less complex. It may be due to the fact that understanding many of the most exciting things about these organisms often requires context.

An appreciation of lichens, for example, requires an understanding of biological concepts that may not be common knowledge. See, a lichen is not a single species, but rather is a collective. A lichen is the product of a symbiotic (interspecies) relationship between one or potentially more fungi and one or more photosynthetic species, usually green algae. The unusual nature of this relationship often only becomes apparent after seeing what these partners look like on their own. When separated, a lichen’s fungal and algal partners do not resemble their product in the slightest! There is no fungi-less lichen in the way that other creatures in symbiotic relationships can be separate and still resemble their original organisms. Let’s say you removed the symbiotic algae from a coral, just as modern ocean acidification does. Before the coral bleached and died, it would still look like coral. Alternatively, if you removed all the gut bacteria from a human, they wouldn’t be healthy, but they would still look like a person. For lichens, this is not the case.

Lichens are also biologically interesting as they can be indicative of specific environmental conditions. Icmadophila ericetorum, affectionately nicknamed ‘Fairy Barf’ by lichen enthusiasts, is a light green crust lichen flecked with tiny pink reproductive disks. It is found in wet areas on rotting wood or soil beds and is relatively common here on the island. Heterodermia sitchensis or ‘Seaside Centipede Lichen’, on the other hand, has an incredibly specific habitat, growing only on the lower branches of shoreline Sitka Spruce trees that have enhanced nitrogen thanks to the excrement of nearby wildlife. The only known populations in Canada are within or near Pacific Rim National Park Reserve! Lichens of the genus Usnea may be familiar to you already – these lichens’ common name is ‘Old Man’s Beard’ as they are long, stringy, and bushy. You don’t have to go very far to see Usnea, as they’re all around this area! If you didn’t know better, you might mistake Usnea for moss, as it hangs in trees. However, Usnea is much lighter green and feels dry to the touch. Usnea lichens are excellent bio-indicators, meaning they provide information to ecologists about the area where they are living. Their hair-like structure means they have a large surface area, making them sensitive to air pollution. In terms of conservation, it is practical to monitor lichens as they are perennial, stable throughout the year, and are bio-indicators of diverse forests.

If not interested in conservation for an organism’s cuteness, exotic colouration, or extraordinary size, people often seek information about its use to humans to determine its significance. I would argue that the value of an organism lies not just in its edibility or medicinal use. Lichens and other small and fascinating organisms (slime molds, mushrooms, algae, etc.) are evidence of the connections between bigger things. These more inconspicuous organisms show ecologists minor differences in environmental conditions they may have overlooked, provide animals with food and building materials, and facilitate nutrient cycling and fixation.

If nothing else, I urge you in your day-to-day travels here or elsewhere, to grant lichens a moment of your attention only so you might notice, even if they’re not as striking or glamorous as sea stars or hummingbirds, that they too are intricate and beautiful. Furthermore, the more time you spend learning about how these small things go about their lives and the more questions you ask, the more interesting they will become.

Written by: Sam Pedersen, Summer Intern 2020